NORTHERN MANSI

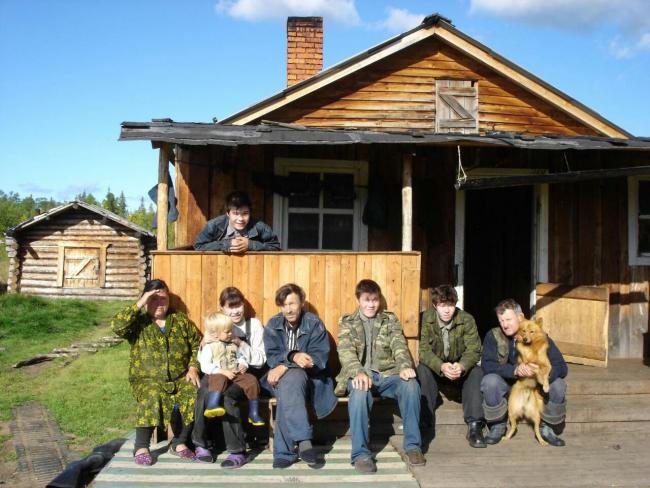

Apart from those Mansi who live in the regional capital, Khanty-Mansiysk, today most of the 9000 Mansi live in the northwest part of Khanty-Mansi Okrug-Iugra, along the Northern Sosva, Lyapin and upper Lozva rivers. It was not always so. The northern Mansi group emerged relatively recently, when a Khanty population, already resident in the Sosva region, received emigrant Mansi groups, who had been driven out of their lands on the western slopes of the Urals. Russians, pushing back the Tatars, had expanded into the Perm region, hastening the northward expansion of some of the Komi population then living in the Perm region, putting pressure on Mansi living north of Perm. When the Mansi Pelym principality, a Tatar ally, was liquidated, people from Pelym, Lozva and Konda also moved northwards and took part in the formation of the northern Mansi. The northward emigration of Mansi from these territories to Northern Sosva and Lyapin Rivers continued into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.1 Today, these Northern Mansi constitute the vast majority of the Mansi population, with some remnant populations in the south. Over the course of the last four centuries, all have been subject to enormous acculturative pressures. Today many northern Mansi live in sizeable villages, while some maintain seasonal or year-round extended family settlements like Khanty.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the rise of nationalism in Hungary and Finland led scholars in those countries to explore the remote Finno-Ugric peoples to whom their languages were related. Important work among the Mansi was done by the Hungarian scholars, Antal Reguly and Bernat Munkácsi who traveled to Siberia in the nineteenth century. In Finland, the Finno-Ugrian Society was founded in 1883, by which time August Ahlquist had already made three trips to Siberia and completed very serious work on the Mansi; he was followed by Artur Kannisto who, among his other work, collected Bear Festival songs from Konda Mansi and from the Northern Mansi. Today the work of revival and scholarship is carried on by indigenous Mansi scholars. The late Yevdokia Ivanovna Rombandeeva, a Mansi folklorist and linguist, among many other accomplishments, translated into Russian and published Mansi Bear Festival songs transcribed by the Hungarian scholar, Bernat Munkácsi. 2 A contemporary Mansi scholar and NSF research team member, Svetlana Popova, made essential contributions to the description and video presented here. 3

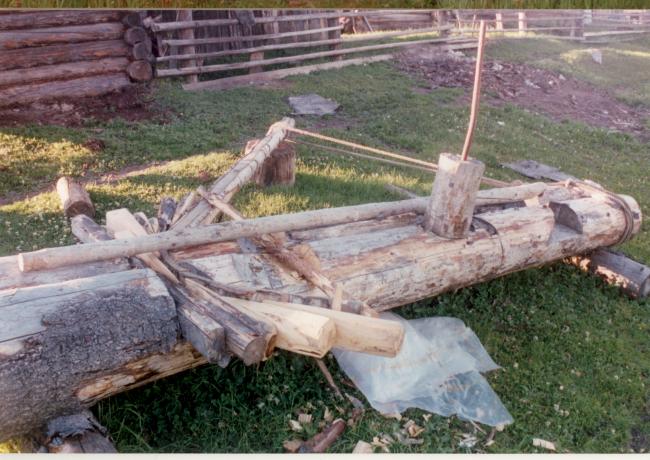

Some of the similarities between the Northern Khanty and Northern Mansi Bear Festivals may be accounted for by the historical amalgamation of a resident northern Khanty population with Mansi groups coming from the west and south. Chernetsov distinguished between sporadic bear festivals, held after the killing of the bear, and much larger, social gatherings of which the bear festival was a part which were held periodically at places like Vezhakory. These periodic festivals, associated with the winter and summer solstice, were known as the “big dances” or “great dances,” and functioned to renew the bonds between the groups and affirm the social order, of which the bear was the symbol. In every village, there was a main house for celebration, and historically the preservation of images of spirits and offerings. In Lombovozh it was the house of the Sheskin princes, but when it was destroyed, a new one was built in its place. The Lombovozh bear festival highlighted in the accompanying video celebrated the inauguration of the new big house. Today the Mansi only celebrate the sporadic variant, the last periodic festival having been celebrated in 1977. Both versions feature the Sacred Night, but different deities are present. 4

THE NORTHERN MANSI BEAR FESTIVAL

According to S. Popova, in every Mansi village, ”The structure of the sporadic bear festival among Mansi is based on the following elements: locating the den; extraction, delivery and meeting of the bear in the settlement; preparatory actions; cleansing and fortune telling; the festival itself, accompanied by chants, dances and dramatic performances; the rite of animal sacrifice; sacred night with the introduction of the spirit patron saints of the nay-ōtyr’ov, literally, ‘Heroines- bogatyrs’, in an anthropomorphic image and ancestors of the clans in the hypostasis of an animal; "animal and bird" dances; the destruction of the [bear’s] table; the removal of the bear head, the farewell and the commemoration.” 5

The Northern Mansi Bear Festival is clearly divided into two parts, unequal in duration and significance. The first is a section of songs, skits, and both men’s and women’s dancing, accompanied by music. Here there are several important differences with the Northern Khanty. Perhaps the most important of these is that at present, as among the Yugan Khanty, death has taken the last of the elder singers of Bear songs; this last singer is shown in the video below inviting the deities to the Sacred Night. The texts of such songs have been recorded by the Finnish scholar Artur Kannisto6 and made available in both Mansi and Russian, so their general themes and structure known.7 Among the most important of these songs is the song that tells the Mansi story of how the bear was lowered from the Skyworld into this world, a version of which you can read in English for the first time here. The comic skits are also well-documented, including their texts, and have been published recently.8 While both Northern Khanty and Northern Mansi will offer an animal as a blood sacrifice, the Northern Khanty do so (in this case a reindeer) before the actual festival begins and away from the festival house. The Mansi also sacrifice an animal (at Lombovozh a calf) though not outside but inside the house in the presence of the bear. In at least one Northern Mansi Bear Festival, that at Kimkyasui in 1994, a single woman from Sosva danced what was known as the ‘bear dance’, which was unique and shown in the video below. In the general knowledge, only this woman knew this dance and its significance, and since she has passed away, it has never been repeated. After this dance, it is said, women should no longer dance but only be spectators.

Like the Northern Khanty Bear Festival, the Northern Mansi Bear Festival concludes with the Sacred Night, when deities make their appearance. Each features some common Ob-Ugrian personages, such as the Crane who tries to destroy the bear’s place, and Kaltashch, the great mother, but in both cases some of the deities are local and very specific to each group. The Mansi Sacred Night Performance is distinguished by its clear associations with the Ural Mountains and with times of hostilities. Specific to the Mansi tradition of the Sacred Night, for instance, is the Dance of the Seven Bogatyrs (Warriors), which comes in several parts. The story behind it begins with a hunter, who sees a boat coming from far off. As it approaches, he is terrified to see they are warriors, but they tell him not to be afraid and to accept them as his defenders and patrons, which he does. This set of dances clearly belongs to a period of hostilities, perhaps when the Mansi were allied with the Tatars against the Russians. Another unique figure is Payping Oika, “The protector of the settlement,” who is armed and searches the four corners of the performance space on the lookout for potential attacks. Hont Torum, the God of War, well-armed with clashing arrows, also appears. Tulang urne oyka, The Guardian of the Seven Finger Mountains (the Urals), is always depicted carrying two larch trees.

Finally, when the festival is over, the bear’s male guardians send the women out of the house so the bear can be discreetly carried away to the forest. When the men exit the house, however, they are showered with snow by the women, who cry “Why are you taking away my younger brother?”, and made to circle the house three times. When they are finally able to get away, the men are confronted by Raven, who makes a last try at stealing the bear’s soul before he too is defeated, and the bear successfully returns to the forest. The Mansi Bear Festival thus dramatizes their relationship to the forests and the Ural mountains.

REGIONAL VARIANTS OF OB-UGRIAN BEAR FESTIVAL

Follow the links below to see film and photos that illustrate how the bear festival as practiced today by other Ob-Ugrian peoples in western Siberia.

Northern Khanty Bear Festival

Eastern Khanty Bear Festival

1 Popova, S. 2018. Общая структура Праздника Медведя в Северном Манси. Unpublished ms.

2 Мункáчи, Б. [2012]. Медвежьи Эпические Песни Манси (Вогулов), том. III. Russian Translation, Rombandeeva, E. I. Khanty-Mansiysk.

3 Попова С. А., 2017.Медвежий праздник северной группы манси: языковое табу. Финно-угорский мир. № 3. pp. 102–112; 2015. Роль периодического медвежьего праздника Яныг Йикв в формировании социума северных манси Вестник угроведения №1 (20) 89-100; 2013. Этническая история и мифологическая картина мира манси. Ханты-Мансийск; 2011. Медвежий праздник на Северном Урале. Ханты-Мансийск/

4 Chernetsov, V.N., 1968. Periodicheskie obriady i tseremonnye u Obskikh Ugrov, sviazannye s medvedem [Periodic rituals and ceremonies of the Ob-Ugrians, connected with the bear]. In Congressus Secundus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarium. Pars II Acta Etnologica (Vol. 10, p. 16). Societas Fenno-Ugrica Helsinki.

5 Popova, S. 2018. Общая структура Праздника Медведя в Северном Манси. Unpublished ms.

6 Каннисто, А [2016]. Мансийские песни о медведе в записи Артура Каннисто. Перевод с немецкого языка Н. В. Лукиной. Томск.

7 Мункáчи, Б. [2012]. Медвежьи Эпические Песни Манси (Вогулов), том. III. Russian Translation, Rombandeeva, E. I. Khanty-Mansiysk

8 Каннисто, А., Лиимола [2016] Драматические представления на медвежьем празднике манси. Переиод с немецкого языка и публикация Н. В. Лукиной Ханты-Мансийскю