West Siberia

WEST SIBERIAN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES

Western Siberia stretches from the forested zone of the Urals through the lowland taiga watershed by the Ob and Irtysh Rivers. Central Siberia reaches from the highlands along the Yenesei River eastward to the Lena River Basin. All of these rivers flow north into the Arctic Ocean from mountain ranges far to the south that separate this area from the steppe zone of central Asia.

The oldest language family in this Urals area is the Finno-Ugrian, which has three branches.. Some groups of the Finnic-Permian branch of the Finno –Ugrian language family lived west of the Urals, and eventually settled as far away as the Estonia and Finland. Similarly another distinct language group, the Samoyedic branch, moved north and east eventually settling in the less forested and tundra areas along the Arctic Ocean shores from northern Siberia to west of the Urals, becoming today’s Nenets. The most numerous peoples in the Urals area were from the Ugrian branch of the Finno-Ugrian language family, the Mansi and the Khanty. Genetic research suggests that about 6,800 years ago ancestral populations of Western Siberians mixed with an ancient group most closely related to the modern-day Evenk, and that about 2000 years after that, the Mansi, Khanty, and Nenets began to separate.1 Mansi oral history supports a story of complex origins, telling that when they resettled in northwestern Siberia, they met and intermixed with another people already living there. The last major separation took place about 2000 years ago when the Magyars separated from the Khanty and Mansi living in the Ob’ River basin and moved westward, eventually settling in Hungary. After that, the largest tribes, the Khanty and Mansi, remained in the basin of the Ob River, and today are known collectively as Ob-Ugrians.

Far from being isolated, most of Russia’s 40 northern indigenous tribal peoples experienced migrations, displacements, and significant historical impacts from other populations. By the 10th century Russians in Novgorod were already trading steel war implements with Mansi who were then living on both sides of the northern Urals. The greatest impact came with the 13th century expansion of Mongol-Tatar armies across the steppe zone. They displaced the Yakuts northward, dividing widely scattered Evenk groups. Eventually the Mongol Khans exerted hegemony over the Russian princedoms that lasted until 1480. By the time of the Mongols, Ob-Ugrian Khanty and Mansi had settled throughout the basin of the Ob-Irtysh river system, whose tributaries drain the West Siberian Plain. For a long time the Ob-Ugrians had been middlemen, trading furs to the south through Mongol territory and across the northern Urals into Russia. The competition for fur territories was not without consequences. During the medieval period, they lived in fortified towns in a kind of feudal, socially-stratified society of chieftains or “princes , a warrior caste, and adjacent population. They paid a tax in furs, first to the Mongols—the fur tax is called iasak, which is a Turkic word—and then later to the Russians. After 1480, Russians forced the Mongol-Tatars to withdraw eastward toward and across the Urals. The Mongols divided their territories around the Urals and in Siberia into different khanates, over which they still exerted influence until a series of Russian campaigns in the 16th century displaced them. Nevertheless, the Tatars left their mark on Ob-Ugrian culture in gender roles, dress, and material culture.

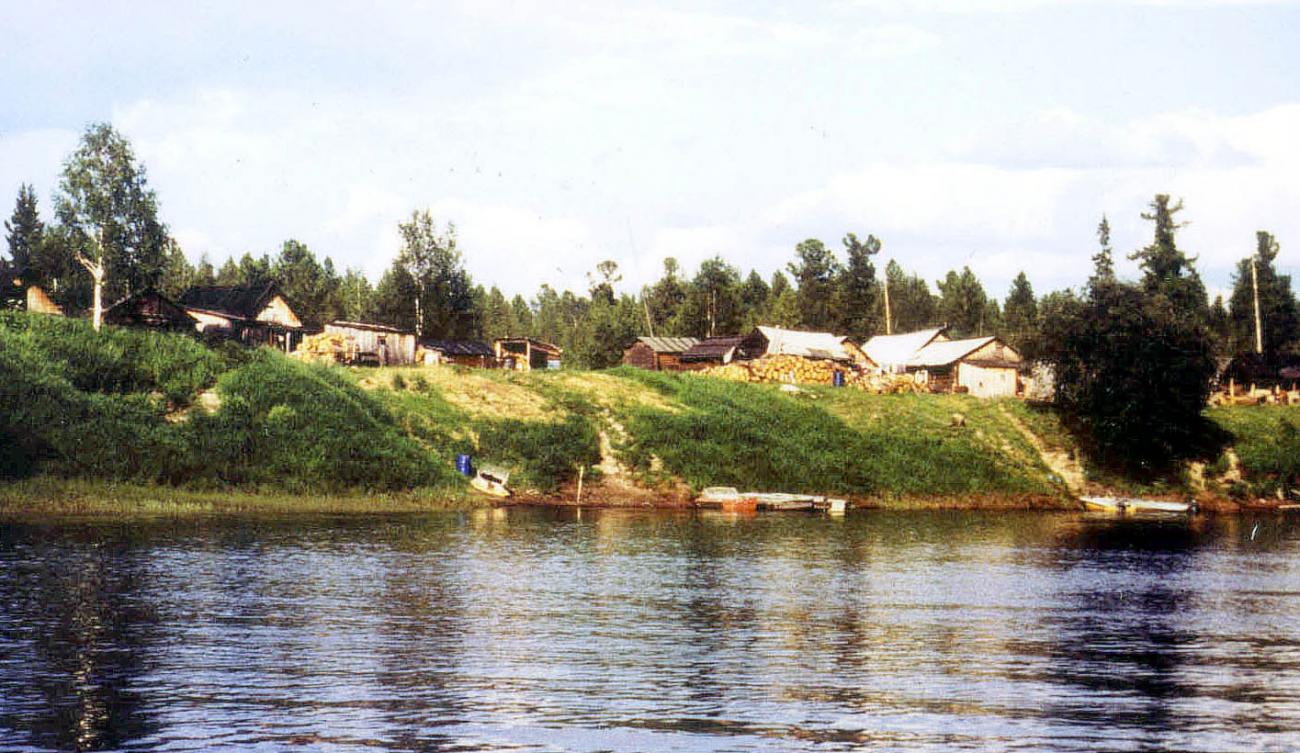

The establishment of Russian hegemony throughout Siberia saw the demise of the Ugrian princes and the dispersal of the population from fortified towns to widely-scattered settlements. Today Khanty and Mansi live principally by fishing, hunting, trapping and small-scale reindeer herding, with varying emphasis in local economies. Local group identity, usually based on river systems, was reinforced through use of the Russian volost (district) system to administer the collection of fur tribute. The eighteenth century also saw aggressive Christian proselytizing and direct attacks on indigenous religion. Limited reindeer domestication north of the Ob’ River grew to large-scale reindeer husbandry after 1700. Southern Mansi, living along the Pelym and Konda Rivers, and Southern Khanty groups, living near Tobolsk, were all assimilated by the early 20th century. The coming of Soviet power significantly reshaped indigenous economy by industrializing traditional subsistence harvest activities, introducing wages and currency, shifting the sense of property, and later introducing resettlement campaigns. The suppression of indigenous religious practices, the introduction of compulsory education, and acculturation campaigns that targeted a number of customary practices all substantially impacted indigenous culture. In the late Soviet and contemporary periods, state exploitation of oil and gas in Ob-Ugrian lands became the principal source of Russia’s wealth, but it has had devastating consequences for Western Siberia’s indigenous peoples. 2

OB-UGRIAN BEAR FESTIVAL AS IDENTITY SYMBOL

It is probable that the Ob-Ugrian bear ceremony, as we know it today for the Northern Mansi, Northern Khanty and Eastern Khanty of Siberia, played a prominent role throughout this history of dispersal, transformation, aggression and repression. Early in the current era a style of bronze casting emerged in the Perm region which featured bears prominently among other animal figures, and may signal an important turning point in the historical development of the Ob-Ugrian Bear Ceremony. Among the Mansi and Northern Khanty, Chernetsov distinguished between two types of festivals involving the bear—the sporadic and the periodic.3 The ‘sporadic’ bear festival was performed after a bear was hunted and killed. For the Northern Khanty and Mansi, the final night was designated the “Holy Night” and patron spirits came to dance before the bear. Some of the animal dances Chernetsov interpreted as having a totemic character. The ‘periodic’ bear festival was held seasonally, in association with the summer and winter equinoxes, in specially designated villages to which the population of clan relatives was obliged to come and participate, bringing with them the images of their clan ancestors and participate. These ceremonies, according to Chernetsov were related to the complex phratrial-clan organization of the Mansi. These occasions were longer and more complex than the sporadic bear festival, because additional features having to do with social relations were added. This type of celebration does not seem to have been part of the Eastern Khanty tradition. Chernetsov hypothesized that the sporadic festival represented a devolution from the periodic festival, but the reverse is also not unlikely: that the simpler, post-hunt bear festival evolved, with the addition of clan-related elements, to become a key identity symbol that functioned to integrate various local Ob-Ugrian villages and families. 4, 5

MAIN FEATURES OF OB-UGRIAN BEAR FESTIVALS

While Ob-Ugrian bear ceremonialism incorporates the whole activity from the hunt, to the communal celebration, to the disposition of the bones, we attend here only to the basic structure of Ob-Ugrian Bear communal celebration, which focuses on some generally shared features, below. The Ob'-Ugrian bear ceremony is not a "sacred" ceremony or religious ritual, in the sense of being closed to strangers and the uninitiated. It is a public community celebration, hosted by members of the community, conducted according to a general formal pattern elicited from community memory, to which non-community members can be invited, and with permission it can be photographed. Although not a religious ritual, it nevertheless demands respect from all who attend.

1. DEFINITION OF PERFORMATIVE TIME AND SPACE. Traditionally, the length of the celebration is determined by the age/gender of the bear taken -- 3 days if a cub, 4 days if a female, 5 days if a male. Within the frame of the festival proper, the festival "night" is defined not by the diurnal cycle but by performative elements, such as special songs to wake the bear and put it to sleep. The festival takes place in the home of the hunter, though it may also be hosted in another house which is larger. Northern Mansi communities had a tradition of building a special, much larger house for community celebrations. The Bear, richly clothed and adorned according to its gender, is seated in the place of honor on the sleeping platform or raised table opposite the door or in the special corner reserved for icons. Among Eastern Khanty a special house is built for the bear. The audience is gender-segregated and lines the walls, defining the performative space in front of the bear.

2. SONGS. The festival proper opens with songs, the first of which retells the story of how the bear came to be lowered down from the sky by his Heavenly Father, of his travels and life on earth and how he came eventually to be in this place where he is being honored. A number of songs follow and make up the most important part of the ceremony, often quite long. There are regional variations in singing, but singers disguise themselves with special costumes and cover their hands, and use a staff to keep rhythm. Special songs for waking the bear and putting him to sleep each ”night” are accompanied by the ringing or other jingling sound produced by a small bell or other means attached to a string fixed near the bear and pulled rhythmically by the singer. At the end of each ceremonial “night,” the bear is put to sleep with a special song and its head entirely covered by a scarf.

3. DANCES. Both men and women dance, though separately. Dances are roughly mimetic. Men dance imitating the gait of the bear or a hunter by stepping heavily forward in a crouched position. Women imitate gathering birdcherry or other activities, and must dance before the bear with the heads entirely obscured under a large shawl draped over their heads and supported by outstretched arms. Men’s hands are covered by gloves, women’s by the ends of their shawls.

4. SKITS. Clowning is a required and important part of the bear festival and accounts for the characterization of the event in its Russian name, as “bear games”. Certain skits are well-known and seem to be frequently performed throughout the entire Ob-Ugrian area and persist even to this day. Many of the skits involve courtship, marriage or sexual behavior, feature erotic humor, and often use a stick or pole as a symbolic phallus. Clowning is done in a special costume that consists of a long, brown hooded felt garment, often used as an inner coat under the colorful thigh-length parka (malitsa). Like singers, actors wear masks made of birch, a portion of which has been cut out to form a large nose, and usually disguise their voices by speaking in falsetto.

5. DIVINATION. Various forms of divination are employed to gain hunting luck, to determine who will get the next bear, host the next festival and how soon (which, of course, is also a matter of hunting luck).

6. FEASTING. Elaborate feasting with a plentiful table, even to the point of emptying the larder, is essential. Feasting takes place while the bear "sleeps." In customary Ob'-Ugrian fashion, men and women sit separately. In ethnographic literature, provisioning guests was of such importance that that a host might call on family and friends to supply food and drink to make up his own deficit. And we should not forget that the bear is provided with its own portions of bread, berries, meat, candy, vodka, and tobacco, so as to share in the feasting.

These elements are the core of Ob-Ugrian Bear Festivals, but the peoples of western Siberia have local variations of the Bear Ceremony, for example, requiring an animal sacrifice before or during the ceremony. Mansi scholar Svetlana Popova sees in the Bear Festival elements of the traditional funeral. “Every day, in the morning and in the evening, throughout the whole holiday, hot food is put on the table in front of the head: meat, fish, and everything that stood before and is already cold is passed on to the common table. Thus, allegedly, the beast takes part in the universal meal. But if one looks deep into the tradition, there is an analogy with the rituals of the funeral ceremony: Mansi ‘invite’ the deceased relative to the daily meal twice a day - in the morning at sunrise and in the evening at sunset, this time of day correlates with the transition state.” 6 The sporadic bear festival as practiced today in western Siberia, illustrated with video, photos and texts, is described in the following pages.

REGIONAL VARIANTS OF OB-UGRIAN BEAR FESTIVAL

Follow the links below to see film and photos that illustrate how the bear festival as practiced today by different peoples in western Siberia.

Northern Mansi Bear Festival

Northern Khanty Bear Festival

Eastern Khanty Bear Festival

1 Wong, Emily H M et al. “Reconstructing genetic history of Siberian and Northeastern European populations.” Genome research vol. 27,1 (2017): 1-14. doi:10.1101/gr.202945.115

2 Wiget, A. and O. Balalaeva, 2011. Khanty, People of the Taiga: Surviving the Twentieth Century. Fairbanks: U of Alaska P, 2011.

3 Chernetsov, V. N. 2001. Medvezhii Prazdnik y Obskikh Ugrov. Ed. N. V. Lukina. Tomsk: Tomsk U .P.

4 Spicer, E.H., 1971. Persistent cultural systems. Science, 174(4011), pp.795-800. See also: Karjalainen, K.F., 1922-1927. Die Religion der Jugra-Völker: 3 volsI. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.; Karjalainen, K.F., 1995. Religiya ugorskikh narodov [Religion of Ugric peoples]. Translated from German by NV Lukina, 2.

5 Ortner, S.B., 1973. On Key Symbols . American anthropologist, 75(5), pp.1338-1346.

6 Popova, S. “Структура церемонии медвежьего праздника северных манси”. Unpublished ms.