Johnassie Ippak: Sea ice observations

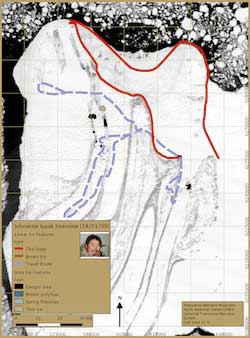

Johnassie Ippak originally learned from his father where to hunt in the Belcher Islands. Hunters travel on sea ice floes to reach the seals, geese, ducks, and whales that they rely on for food. During the interview for the Sanikiluaq Sea Ice Project, Johnassie indicated that sea ice around the islands is becoming more dangerous, and he marked the changes on the map viewable below. In recent years, Johnassie has had to alter his travel routes and scout new hunting grounds because of the changing sea ice and weather conditions. “The ice is not frozen like it used to be,” he said.

Changes in sea ice extent

Interview videos: Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3 - Part 4

Sanikiluaq hunter Johnassie Ippak discussed sea ice conditions in January 2009, when he was interviewed by Miriam Fleming, with translator Dinah Kavik. Photo credit: Miriam Fleming; video credit: Caroline Meeko, Jr.

Up until 2006, the ice floe edge that Johnassie hunted from extended past the northeastern area of the Belcher Islands, just beyond the Bakers Dozen Islands. Since 2006, however, the ice floe edge has retreated south, hugging the coasts of Flaherty, Wiegand, and Johnson Islands. In the past, Johnassie had done most of his winter hunting in the northern part of the Belcher Islands, but he cannot count on safe ice conditions. “We cannot travel further north now, like we used to,” he said.

Because of changing sea ice conditions, Johnassie can no longer use his father’s traditional hunting grounds, and he has had to locate new winter hunting areas in the southern portions of the islands. Johnassie’s map shows how he has altered his hunting routes in response to changing sea ice conditions. He now has to concentrate on the coasts near the communities to hunt for food.

In addition to hunting from ice floes, Johnassie also discussed hunting seal at polynyas, which are areas of open water surrounded by sea ice. Some of the polynyas used to freeze over, but some now stay open all winter.

Changes in sea ice thickness

Interview videos: Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3

Sanikiluaq hunter Johnassie Ippak described photographs of sea ice in January 2009, when he was interviewed by Miriam Fleming, with translator Dinah Kavik. Photo credit: Miriam Fleming; video credit: Sarah Kudluorak, Jr. and Caroline Meeko, Jr.

The ice around the islands begins to freeze in December, and by late December and early January, the sea ice is usually thick enough to ride a snow machine on. Johnassie said, “Ice would get about two feet thick at its thickest, years ago, at this time of year, when the ice was still good.”

Johnassie also indicated that changes in ocean currents are affecting the thickness of the ice, perhaps causing earlier melting during spring. In early spring, the sea ice begins to melt from underneath before it breaks up. During the Easter season, Sanikiluaq residents used to be able to reach the Nunavik mainland to the east by traveling over the sea ice. But for the past three years, no one has been able to make that crossing.

Hunter Johnassie Ippak shared his sea ice observations as part of the Sanikiluaq Sea Ice Project. Photo credit: Miriam Fleming

Hunter Johnassie Ippak shared his sea ice observations as part of the Sanikiluaq Sea Ice Project. Photo credit: Miriam Fleming View a full-size map of Johnassie Ippak's sea ice observations, with a key to his notations and what they mean.

View a full-size map of Johnassie Ippak's sea ice observations, with a key to his notations and what they mean. View a full-size map of Johnassie Ippak's sea ice observations overlain on a Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellite image.

View a full-size map of Johnassie Ippak's sea ice observations overlain on a Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellite image.