As part of the ELOKA mission of ensuring data sovereignty for Arctic residents, ELOKA helped create online atlases for two groups of Indigenous people: the Yup’ik in Alaska and the Evenki in Siberia, Russia. These atlases use an interactive platform to upload, document, and share the knowledge, places names, and culture of these communities. Recently these atlases have been translated from English into Yup’ik and Russian to support increased local use of these tools.

These digital resources transmit important cultural knowledge across Yup’ik and Evenki generations, and to the broader public. “The Evenki Atlas is a small communication point that has brought back self-esteem and value to these smaller Indigenous cultures in Siberia,” said Tero Mustonen, the president of Snowchange, a Finnish organization devoted to local and Indigenous cultures and traditions in the Arctic.

Evenki Atlas

About 38,000 Evenki live in small villages or nomadic tent camps across 7 million square kilometers (5.7 million square miles) from central Siberia to the Pacific Coast. “Outside of Russia, we can celebrate the English version, but it doesn’t really make a lot of sense for the Evenki in English,” said Mustonen. Snowchange staff spent over a year translating the atlas it into Russian, a common language among Indigenous communities in Russia. A future goal anticipates an Evenki language version of the atlas, when and if resources can be mustered.

“One of the challenges for many international organizations working in the Russian Arctic continues to be the fact that unless good coordination is done, [the organizations] can be seen as negative partners in today’s sociopolitical context. Whatever we think of that context, it’s there. And that influences what can and cannot be done,” said Mustonen. With the support of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Snowchange translated the atlas into its Russian version, helping to avoid misunderstanding between various parties. Since Indigenous rights and land use in Russia have been heavily contested, presenting the Russian version of the Evenki Atlas sends a positive message about their cultural heritage, and how they have maintained their way of life and language. “So the atlas is not against anybody,” said Mustonen, “but for all people who want to learn about the Evenki and their unique way of life.”

In 2019, the Evenki Atlas went live in its English version. On January 22, 2020, ELOKA published the Russian version after spending several months implementing the translation within the foundational Nunaliit software.

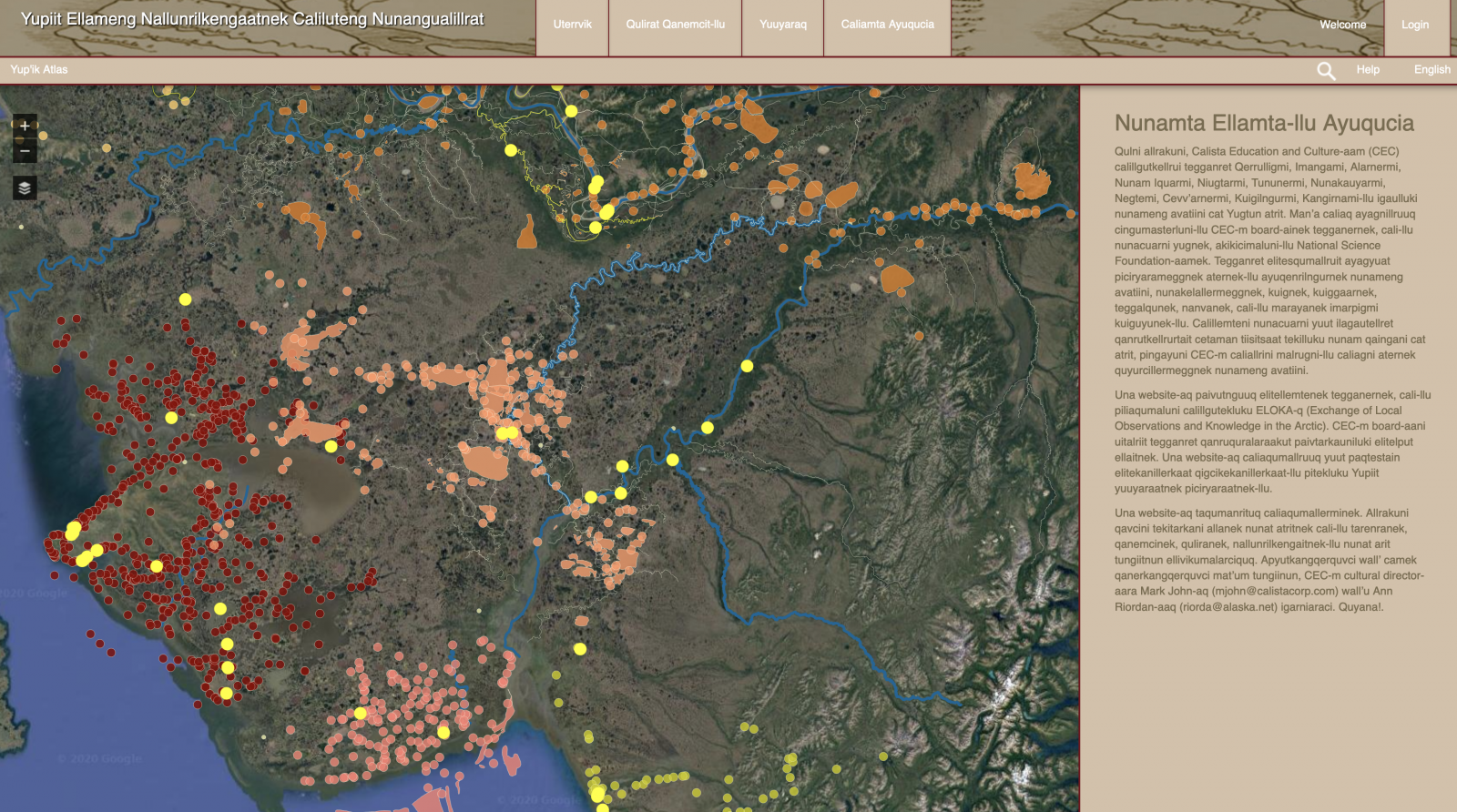

Yup’ik Atlas

The Yupik Atlas hosts place names data from a project that began in 2000, when the Calista Elders Council (CEC) worked with the Bering Sea Elders Group to garner more than 3,000 Yup’ik place names of value and cultural importance. In 2012, ELOKA and CEC published the Yup’ik Atlas online in English; since then, it has grown to house more than 4,000 place names, as well as recordings of stories, oral history interviews, traditional songs and dances, and photographs.

In 2017, the Yup’ik Environmental Knowledge Project, which hosts the Yup’ik Atlas, also began collaborating with the Lower Kuskokwim School District, so teachers and their students could learn to use and upload content to the atlas. With input from ELOKA, the district developed curriculum around the atlas to allow middle and high school students to collect and share their own stories about Yup’ik history and culture. In the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, children learn Yup’ik as their first language and out of more than 23,000 people, 14,000 speak the language.

In late 2019, ELOKA began to work with CEC to implement a Yup’ik translation of the atlas to broaden its use as a tool for language learning. Alice Reardan, who works with CEC to translate oral history and place names, translated the text into Yup’ik, while ELOKA set up the technological infrastructure. The Yup’ik language version of the atlas was released in March 2020. “Yup'ik is still widely used in the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta, and we especially wanted students to have access to a Yup'ik version so that they would have an opportunity to work in the Atlas in their first language,” said Ann Riordan, a cultural anthropologist who also works with the CEC to document Yup’ik knowledge.

Not to be taken for granted

In Alaska, from the base of permanent settlements, Yup’ik continue to hunt, fish, camp, and travel on land, drawing a deep, intergenerational knowledge of and relationship with the land, water, and animals. In Siberia, the Evenki lead a nomadic lifestyle that keeps their people in the forest. This nomadic way of life is extremely rare, and the Evenki hold this tradition and lifestyle fully. “All these systems, these Indigenous ways of life, in my opinion have inherent value,” said Mustonen. “They are unique. They are under threat from multiple sources. So anything we can do on their terms, provided by the knowledge holders and their people that supports what they are trying to maintain and revitalize is positive.”