Lower Kolyma Fisheries

Introduction

The Lower Kolyma region is widely known for its iconic nomadic reindeer communities. The major Siberian river, along with hundreds of smaller streams, lakes and the Arctic Ocean coast is home to rich and diverse fish species. These fish have been the food security and cultural staple for the region’s communities for millennia. In this part of the Snowchange Kolyma ELOKA pages we explore some aspects of the Indigenous fishery in the region and some of the drivers of change affecting it. Most of the materials here discuss freshwater harvests.

In order to get a sense of some of the smaller streams that are prominent in the region, you can click on a video clip to see the Turvaurgin community representatives boating upstream on the Chukotskaya River.

Species Harvested in Kolyma

Main fish harvests in Kolyma focus on broad whitefish. Similarly, nelma is taken as a by-catch even though measures to protect the species have been put to place. According to the UNEP—financed ECORA project:

“The main commercial species in Nizhnekolymsky (Lower Kolyma) region are broad whitefish, omul (Arctic cisco), muksun (whitefish) and European cisco. Nelma is very small in number and is not fished purposefully, but it regularly gets caught in the nets. As stated by the expert Matvey Tyaptirgyanov, the abundance of other species is also reducing gradually and their populations are in a tense condition; although local fishermen have other opinion and believe that the state of commercial species, except nelma, doesn’t arouse concern. Vice versa, they have been repeatedly asking for larger fishing quotas, but as long as the quotas are given by the federal authorities, the interests of fisheries are not taken into account. Rapid increase of Siberian salmon population has been registered lately (in mid-2000s). Millions of Siberian salmon hatchlings were released in the Kolyma in 1999-2005; the return of mature individuals is being observed now, which proves the species’ successful stocking. Still, the fishermen are dissatisfied as long as Siberian salmon is regarded as a competitor to whitefish.”

Traditional and Historical Methods

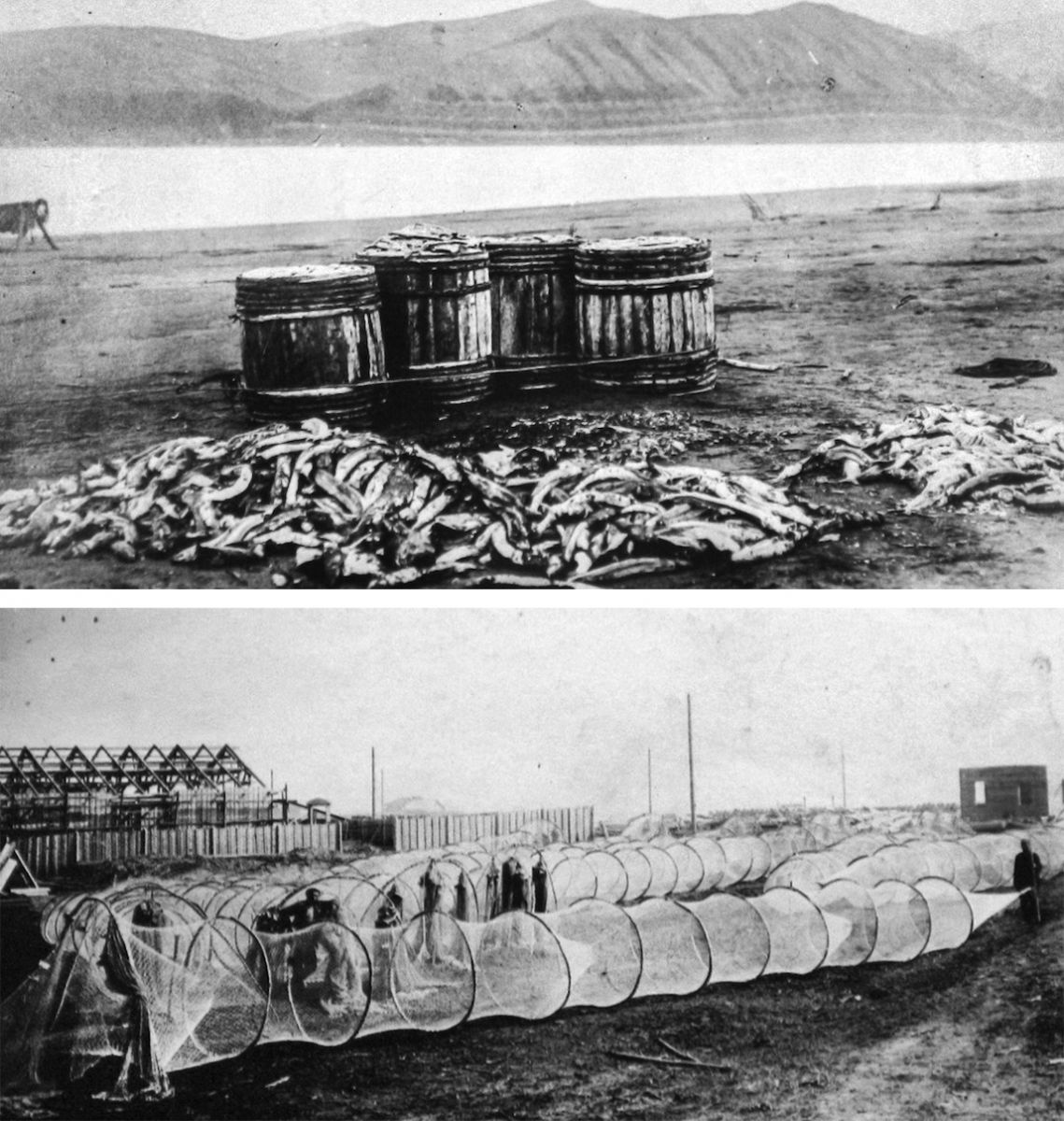

The Arctic Ocean coasts of the East Siberia and Laptev Seas as well as the inland water systems have provided for the Indigenous Chukchi, Even, tundra Yukaghir and Sakha-Yakut in the region for hundreds of years. A glimpse to the historical abundance of stocks is visible in the photos from 1800s and early 1900s.

These two photos highlight some of the early 1900s harvests from Laptev Sea, west of Kolyma, but with a similar style of fish traps in use. While this was most likely already a collective farm fishery of the Soviet period, the methods have been preserved from a long time ago.

A set of photographs, originally recorded as a part of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1897-1902) and made available here thanks to the Institute of the Indigenous Peoples in Yakutsk, documents the subsistence fishery along the Kolyma at late 1800s. The amount of fish are superb. Traditional hand-made boats and dugout canoes constituted the open water mobility to the fish traps and traditional harvest locations in the region.

Subsistence Harvests

The subsistence or household harvests of fish mostly target broad whitefish and muksun species. Other fish, such as northern pike and European cisco are also utilized.

In the summer, families and communities have specific net locations either on the Kolyma, or many of the smaller streams in the catchment area and in the tundra rivers. Wealthier people have a fish base, sometimes utilized by a family, next to the summer net harvest areas.

In the winter, subsistence fishery focuses on standing nets under the ice. Ice depth can easily reach 2.5 meters, so setting the nets and checking them is a considerable work process. Usually in the winter nets are checked a few times a week.

A Special Insert: Harvest of Carp in Yakutia

One of the most unique ways of winter subsistence fishing takes place in Sakha-Yakutia, mainly on the lakes of the taiga forested zone in the winter time.

First, iron and steel ice picks are used to make hole in the thick ice. Great skill is required to penetrate sometimes 2.5 meters of ice.

Secondly, unique fishing nets with a loop and a long pole are lowered into the ice hole. The loop is then rotated on a circular motion close to the bottom of the lake.

This is done to capture karas, a carp species that goes to a status of a hibernation during the extreme winter temperatures of Yakutia. The swirling motion of the pole-loop then brings them to the surface, where they can be harvested with the loop net attached to the pole. Karas is a national delicacy of the Sakha people of Central Yakutia.

Commercial Operations

In Lower Kolyma there are a number of operators conducting commercial fisheries. These include for example:

- The Cooperative of Podhovsk

- The Nomadic Community of Turvaurgin

- The Nomadic Community of Nutendli

The commercial harvests are affected by a number of factors, including closures of harvest due to fish conservation, fish stocking, hydropower impacts from upstream, capacity to process and store fish, and delivery of the catch to central Sakha-Yakutia or Moscow markets.

To assess the level of commercial harvests, for example the community of Turvaurgin, based in the village of Kolymskaya, produces annually roughly 100-130 tons of fish of various stocks.

The village and cooperative of Podhovsk, located close to the Kolyma delta, has a population that derives from the Russian Old Believers and Cossacks of old. Due to intermarriages, many of the families have mixed heritage and links to the surrounding Chukchi and Yukaghir communities.

Podhovsk was a major Soviet commercial collective farm and the cooperative continues the commercial fishery on Kolyma. Seining is a major open water season method of harvests. The biggest seine in the cooperative is 800 meters wide, and is used on Kolyma to catch European Cisco. The biggest single catch has been around 71 tons on a pull. In the 1930s and 1940s seines were usually 350 meters long.

A member of the cooperative from Podhovsk describes the seining:

“Most of the catch places are at the Kolyma delta. We put the seine twice a day into the water, in the morning and in the evening. One team has five to six people. Two people stay on the river shore. They hold onto to the ‘shore rope,' which in Russian is klyatch. When we set the nets, two people hold on to the pulling rope, in Russian fal. A rope is attached to the upper end of the net which stabilizes and opens the seine. Then we start to feed the seine into the river. There is a boat which is drifting at front and it has one person. Then there is another boat, also with one person and the seine. We always set the net against the current. The first boat acts as a pulling vessel. It pulls the second boat, where the seine is located. The seine opens into the water during this process. The boat travels in the direction of the river. We move with the river about 300 to 400 meters and try to catch the fish. Then after a certain period we pull the seine to the shore. At the end of the seine there is a bag where the potential fish have ended up. We do all this by hand, in traditional methods, just like the Ancestors did.” (Snowchange Podhovsk Oral History Tape 2006)

The community members take great pride in being commercial fishermen, as is obvious from one of the oral histories from Podhovsk:

“Of course I am very proud of being a fisherman. I belong to a family of fishermen and we are the direct descendants of the Cossacks. I used to work elsewhere but then I realized I cannot live without fishing.” (Snowchange Podhovsk Oral History Tape 2006)

Freezing in Permafrost Cellars: A Photographic Journey

One relatively unique method of commercial fishery in Lower Kolyma is the use of permafrost cellars as a seasonal storage of commercially harvested whitefish. This set of photos describes the process.

Standing nets are checked usually twice a day at the Chaigurginoo fish base of the Turvaurgin community. The main target of harvests is the broad whitefish.

Once the fish are released from the nets they are transported to the fish base with small boats.

From the boats, fisherman take the fish to the underground cellar, approximately 10 meters underground, to be frozen. Later in Autumn, the fish will be transported, often by helicopters, to the commercial retailers and further to Yakutsk.

For the winter, there are 30 to 60 standing nets for the commercial harvests in Turvaurgin. For future, in the fishing sector, the communities plan to increase the capacity of freezing facilities by purchasing commercial quick freezers to improve meat and fish quality.

Preservation of Fish

While the uses of permafrost cellars are excellent to maintain large harvests, other methods of fish preservation in the summer time are in place.

For example, northern pike is dried in the spring and summer.

Along Kolyma camps, the whitefish is cut to be in prime drying capacity for the short summer.

The dried fish is then used as a trail food and a crucial element of the traditional diet in the extremely remote fish bases of the region.

Fish also provides for the rich traditional handicrafts culture of the region.

Environmental and Climate Change in Fishing

As has been noted elsewhere, climate change is a major driver of change in the Lower Kolyma. Other environmental issues ranging from hydropower development to Soviet dumping of waste in the oceans continue to effect fish stocks. In this part some of these issues are discussed.

The materials derive from the on-going oral history work by Snowchange with the Kolyma communities. This is not data of scientific conclusions, rather a discussion of trends and emerging processes.

By-catch of birds

Starting from the fishery itself, it affects the stocks and also there is a minor by-catch impact to water birds as described by the ECORA reports:

“In most cases loons occasionally get into the fishing nets with the mesh sizes of more than 40 centimeters in size. Usually fishermen find dead birds in the nets; birds found alive are killed because it is very difficult and unsafe to take them out of the nets. According to the questionnaires, in 2006 an average harvest per one hunter was 1.8 loons; total 714 birds were harvested in Nizhnekolymsky region. 97 harvested loons were investigated; 39.1 percent of them were Arctic loons, 30.9 percent were Pacific loons and 30.0 percent were red-throated loons. According to the questionnaires, there were single cases in the lower Chukotskaya River when yellow-billed loons got into the nets. Meat of loon is used for eating; their skins are used for making insoles, hats and rugs. Red-necked grebe, and very rarely long-tailed ducks, tufted ducks and greater scaups get into fishing nets south of Chersky on Kolyma. In 80 to 86 percent of cases the birds get into the nets set on the lakes where they either nest or find food.”

Soviet Overharvests

Many of the commercial fishermen who began their careers during the Soviet times explained that the harvests were too big during the collective economy. Especially during late 1980s and early 1990s the harvests of nelma and muksun might have reached up to 1500 tonnes annually, and this is, according to the fishermen, still affecting for example the stocks of nelma.

Hydropower, Disappearing Lakes and Erosion on Coasts and Rivers

Within the Kolyma basin there are major drivers of change for the worsening environmental conditions of aquatic ecosystems. They include:

- Upstream hydropower development affecting fish stocks, spawning and health as well as water levels

- Mining operations

- Climate change impacts such as erosion and melting of permafrost, altering the cycles of water and increasing the organic loading in the river. This has included whole tundra lakes disappearing as the melt proceeds.

- ‘Phosphorous’ luminousness and strange smells on fish

Some of the fishermen remember annual catches of 800 to 900 tonnes of fish, but “due to hydropower” the amounts are lower today. The fish roe is delicate, and the water levels and temperatures need to be stable and natural for the spawning to succeed. Yet the hydropower alters the river levels and thus wrecks the spawning. Many fishermen link the decreases of fish to three year cycles, referring to hydropower impacts from the past to contribute to the low annual levels of a harvest.

Changes on the Ice Conditions

Climate change has contributed to ice thickness and safety of travel on the ice. Especially European Cisco has suffered due to the ice and water temperature shifts. Kolyma may freeze only in November and the open water season continues well into Autumn.

In recent years as in Spring 2016 reindeer herders have lost skidoos and discovered unsafe ice conditions as a part of their reindeer herding in the spring, especially in the Turvaurgin community.

Arrival of New Species

The fish stocks are under change also in terms of the species present. For example the fishermen of Nutendli community have consistently reported through the 2000s and 2010s the presence of marine species within the Kolyma main course, including medusae. Arrival species of salmon, Pacific Herring and other species are reported now yearly, indicating a shift of more southern species expanding in range along Kolyma.

Conclusions: Fishermen Taking Measures to Adapt to Change

The fishermen in the various Kolyma communities have taken steps in the past 15 years to try to address the changes under way, both locally and through international partnerships.

Regionally, for example the fishermen of Turvaurgin have maintained cultural self-imposed limits of harvests in those areas where fish stocks have been observed to be low.

Fish camps have been installed with pilot-style solar panels to decrease the uses of fossil fuels. This contributes also to the prevention of small scale spills from these fuel sources to the tundra and rivers.

Many fishermen welcomed the ECORA project, between 2003 to 2009 and contributed catch statistics, interviews and questionnaires to help assess the situation on Kolyma. While cooperation has proceeded, conflicts over quotas, commercial potential and transport of harvests remain.

Internationally, the fishermen of Kolyma have welcomed the chance to share their oral histories and traditional knowledge in Arctic initiatives such as the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment.

They have worked with Snowchange to share a major document of changes from Soviet times to present, titled “Life in the Cyclic World”,and more recently, reflections of Chukchi and Yukaghir star lore

In September 2016, the Kolyma communities sent a delegation to the Second Festival of Northern Fishing Festival, held in the community of Zhigansk, on the Lena river. This event, which brought together over 50 professional and artisan fisheries around Siberia, and also Sámi, Finnish, the UK and US delegations, exchanged methods and strategies of adapting to the new realities of 21st century Fisheries. A photographic essay is available here.